The place where the water meets the land in Japan is usually rigorously designed. On the shores of California, for example, the sand at the beach is eroded from the cliffs by the waves over millions of years. The sand is fine, and its of the same color as the hillsides. It feels natural, like it all belongs together as part of an ecological cycle. Going to the beach, you stare at the waves consuming now more, now less of the sand near your feet. But like I said, in Japan, the connection is much more engineered.

While this lets down someone expecting a peaceful shoreline, the design solutions provide platforms for a wide variety of activities. The edge between land and sea always feels like its working hard.

In the aftermath of the March 11 earthquake, the northeastern tectonic plate upon which Japan sits sunk into the ocean about 5 m. Currently, many coastal towns experience flooding each afternoon as the tide comes in over the old sea edge. There is a lot of re-building to do. Below you'll find a summary of current ideas about recovery which I overheard at a recent symposium at Kobe University.

This weekend I took a bike ride around Awaji Island. The coastline boasted a whole pallette of different sea wall solutions, as you can see here. The island is accessed by on the north and south by some of the world's largest suspension bridges. This series of images stretches along the southeast coast from tip to tail.

|

| Awaji Bridge, longest suspension bridge |

|

| a fishing pavilion and sea wall in Akashi city |

|

| Concrete tacks have been arranged in two long rows to create a breakwater that can harbor tidal life |

|

| some tidal life |

|

| another option: a concrete sea wall backfilled by a farmer's plot between the wall and the road |

|

| A constructed riparian zone where the river meets the sea |

|

| This water drains from the mountain, is used for the rice paddies, and drains out to the sea |

|

| A seaside park with broad steps down to the ocean, and a constructed jetty for fishing, or just for being surrounded on all sides by water |

|

| This is called the "sunset line." Its a long seawall that's perfectly straight. I guess it faces west. Everyone gets the same view. |

|

| This beach had a series of underwater low walls to break strong waves or currents |

|

| In a natural harbor, the calm water can host platforms for seaweed cultivation |

|

| The Naruto Bridge, under which swirl the famed Naruto whirlpools |

Kobe University is a nexus for disaster recovery, having built up an academic community around this theme over the last 17 years since the Great Hanshin Earthquake. As students and professors visit the Tohoku region, they return to campus and discuss what is to be done. This week and last week I sat in on a series of symposia where academics gave presentations describing what they saw and studied on recent trips to the north. What follows is a summary of what I heard, thanks to the excellent live translating of Liz Maly.

|

| sea, wall, road, city |

In the past century or so, there have been four major tsunamis: The Meiji Tsunami of 1896, the Showa Tsunami of 1933, the Chile Tsunami of 1966 and now the 2011 East Japan Great Tsunami. If there is an offshore earthquake, the delay time between the earthquake and the wave's arrival can be roughly correlated to the tsunami's height. If the delay time is 1 minute, the tsunami may be around 3 m (9 feet) tall. If the delay time is 30 minutes, the tsunami will be more like 10 m (30 feet) tall.

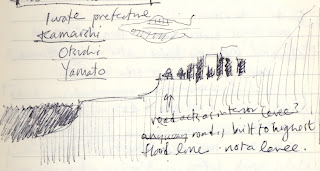

In many places, when a tsunami washed out the road, the new road was built at the maximum height of the water. People build their houses on the other side of the road.

A tsunami wall and a sea wall must be different, because they deal with different kinds of forces. The biggest factor differentiating the two: the tsunami wall has to deal with huge lateral forces, while the sea wall deals almost singularly with vertical forces. Although the reinforced concrete structures fared better than structures of other material, many concrete structures were overturned. Houses and other buildings were ripped out of the ground when the sandy soil liquified and the wave force pushed and pulled on the structure. Another important distinction: if either wall type gets swamped, and the wave crashes over the top of the wall, it quickly erodes the soil behind the wall, causing the wall to break or crumble.

A town lauded for its disaster preparedness, Taro-cho, rebuilt itself behind two separate tsunami walls: one lower and closer to the sea, the other reaching 10m high, pushing a triangle of land against the mountains. The two walls form an X from a bird's eye, and in section create a terraced village. The walls create an strong framework for urban development, sectioning the city into discreet zones. They are pleasing to see. But they did not survive this wave.

A somewhat radical proposal receiving hearings currently is the Super Levee concept. The basic diagram of a Super Levee is if you built a huge cliff next to the sea and then built the city on top of the cliff. It's very expensive, and in its most crude form it eliminates any easy connection to the water for trade, transportation, or leisure. But its designed so that if a wave crashed on its cliff wall, it could break the force, and any water that made it over the precipice would drain away from the edge, through the town, on a 1:30 slope (barely noticeable to a walker).

The zone next to the edge would be mostly landscaped with trees, so that the city begins a bit inland. If you walked from the mountains to the ocean, you would first walk through a dense urban strip, then you might cross a large freeway or road, and then you would find yourself in a broad park-like zone. In a more sophisticated case, this landscaped zone could have a steep slope, effectively creating a large change in elevation between sea and city.

The Super Levee concept is certainly daunting, but there are many villages and towns that will need to be rebuilt in the coming years. I can't help but wonder: can you really prepare for something like this? To what extent? Prior to the recent disaster, Japan's attitude toward its coastlines has been criticized for its unwavering rigor. Visiting Awaji Island, I could see that the edge between the land and the sea doesn't need to be a featureless wall. But I didn't find a place where I'd want to lay a towel and hang out in my bathing suit with some sunglasses on, either. But I did enjoy riding by.

I especially enjoyed this post. Surprise, surprise. I'm particularly intrigued by your sentence - The edge between land and sea always feels like its working hard. I can understand that feeling. I've been on some edges where I can sense work that is slow and steady. And others that feel like stronger efforts of exertion. I look forward to sitting with this idea for a while.

ReplyDeleteHave you heard any talk of protecting development from the sea by means of intentional flooding? Or sea walls designed with an intentional weak link, or means of giving way to direct inundation onto a predefined path?

thanks for posting, slimy! i haven't heard of any intentional weak links or intentional flooding, in japan. i love the idea.

ReplyDelete