|

| Work stops each day at 3 pm these days because of the new high tide |

Prologue: a eulogy

Two landmasses were bearing into one another. This had been going on for a long time. They are like two gigantic wrestlers. One of the masses supports a long, thin island nation of startling beauty and unique cultural habits. The edge of this nation, where the land disappears into the sea, is mostly rimmed in a thin hard shell and a vertical wall, or else a pile of concrete tacks the size of a man, as if they had washed ashore from some sea giants who skipped school. The mass with the island nation capped on one small edge was rising up very very slowly over the other mass which is deep in the lightless dense of the ocean. These two wrestlers. From a certain limited perspective, the two wrestlers seem equally matched, stable, supporting and bolstering one another. We live next to the ocean, we raise gardens in the sea, we feed the world with our delicious harvests. But as we watched longer, we noticed a little twitch here, a slip there: the immense pressure of it. From a certain perspective these short breathy flutters were life-altering events: once or twice in the memory of an old man one of the fighters would slip. And when they slip, watch out, scramble, run for high ground.

|

| Memorial stones for Oshika Peninsula's last 3 tsunamis: 1892, 1933, 1966 |

|

|

Older people remember the last tsunami. In the last century, there have been four destructive tsunamis. To remind themselves, the people on the peninsula near Ishinomaki carved a totemic stone for each wave. The stones bear carved instructions.

The sea will draw away from the land in a great sucking in of breath, and the land mass wrestlers will readjust their grip on one another. Fish will flap helplessly and suck air. The gardens of the sea will be sucked dry, the structure and support of the oyster farmer’s elaborate aquaculture will collapse. Then, the water will surely come back. If you are in a boat, stay in your boat, go out to sea. If you are on land, leave the shore, head for high ground. For the water will come back in a huge black earth filled push back back to the shore and it will bring all of the stuff of the sea gardens with it. It will flood your house, clog your drains, irrigate your inner ear, burst your eardrums. It will fill your sewer with earth and rip your wooden house from its foundations. It will rip away your sister, your mother, out of your arms, even though you followed protocol and even thought you read these warnings. And you will be left on top of a roof which has suddenly become a raft floating upon the cold cold sea. And you may be lost. And you may be found again, warmed, cared for, looked after. Perhaps.

And if you are very very strong, and if you find something to live for, then you can begin again. Even though the wrestlers have slipped. The world is literally different now. The thin ramparts along the beaches seem to have sunk, but its only the new position of the wrestling land masses: the elevation is literally lower now and a new sea wall must be built or else there will be less beach.

What follows is a three part series of images curated to help you understand the situation on Oshika peninsula next to Ishinomaki. They were collected on a volunteer trip to the peninsula on May 4-7, in which college students studying in Japan were supported by the Japan Foundation to help fishermen clean up their beaches and prepare to get back to work. The first, what is to be done? suggests the scale of the destruction. The second, sea gardens, illustrates traditional oyster cultivation, the major industry of the peninsula, which is currently in a critical state. Finally, recuperation by bath documents how people have already filled the basic demand for local baths using very simple technology.

1. What is to be done?

|

| Everything from daily life is mixed thoroughly |

|

| Everything from inside the house has been washed out |

|

| Everything from the industries of the sea has be washed ashore |

|

| There is still so much work to be done |

|

|

It has been two months since the earth shifted and the northeast shoreline of Japan was swamped with forceful waters. “The rising edge of [the North American plate] caused the seabed off the eastern coast to bulge up — one measuring station run by Tohoku University reported an underwater rise of 5 meters — creating the tsunami that devastated the coast” according to an article in the Japan Times "The portion of the plate under Japan was pulled lower as it slid toward the ocean, which caused a corresponding plunge in elevation under the country."

We are starting to clean up, to come up with a plan. The feeling of potential is thick this spring. But there is still so much work to be done. Our fishermen can look out at the beaches and begin to gather together their tools. During the day, there is work to be done, but the evenings are hard. If they can focus on the rebuilding of the oyster reefs and the return to normal life, they can avoid the threat of listlessness, apathy, and depression.

2. Sea Gardens

|

| When outsiders began to help clean up, we began to understand a unique way of working in the sea and a way of life that is now in critical condition |

|

| A. the buoys. After the buoys are separated from the piles of stuff, the fishermen consolidate the buoys on a few beaches |

|

| making huge piles, very satisfying to see |

|

| C. the shells. Also consolidated in low walls |

|

| The strings of shells to be collected are all in Stage I, in which oyster eggs floating free in the ocean bond to these scallop shells strung on long cables. When folded in half, it's reaches about from your shoulder to your knee or thigh. |

|

| After the oyster eggs bond and start to grow, the scallop shells are pulled out and reassembled |

|

| B. the rope. for Stage II: Each shell is bound between the threads of a thick black rope, allowing the oysters to grow large |

|

| This phase takes about 2 years |

The fisherman sketches out the entire system in section and plan using a scallop shell

|

| D. the anchors: I think it's one anchor per buoys, but it may be less, as they are really heavy |

The oyster beds and fish traps make a permeable wall suspended vertically in the ocean for small animals to pass in and out of. They mimic mangroves,

harboring miniature ecosystems. Using these clever and time-tested systems, the fishermen of Ishinomaki feed the world with oysters. However, the total cultivation time is around 2 years. Today, the tsunami may have wiped out the sea's oyster eggs, meaning that the next harvest might not be for 3 years. In Taiwan, oysters are only cultivated for 1 year, resulting in a smaller, less expensive product. At any rate, the fishermen's dependence on aquaculture is both a blessing and a curse.

In a way, they are fortunate. Their reason to live is material, and depends on their own labor. Their lifestyle requires a strong social network because the oysters cannot be raised alone. So these days, friends and fellows stay together and support one another. Many of the fishermen are still swarthy middle-aged fellows, and the industry is strong enough that young people are still becoming fishermen. The rest of the world still wants to eat oysters.

However, as Masahiro Matsuura acknowledges in his blog highlighting the potential opportunity for urban design reform in the region, “Twelve thousand fishing boats, approximately 90% of the registered boats, were severely damaged or lost in Miyagi Prefecture.” Although on the ground the community I visited felt strong and closely knit, Matsuura cites that statistically, “agriculture and fishing were already on the decline in the aging northeast society.” He suggests that “small operations might have to be consolidated by major agricultural firms led by the younger generation.”

This bath is on a hill overlooking the ocean, adjacent to a red cross tent sheltering donated food and supplies and a trailer-like emergency shelter. I think the people who made the bath are SCUBA divers, a slightly different community than the fishermen.

The system is simple. Water drains down the hill in a small creek. The water is collected in the big yellow container. Dishes can be done on the blocky white container. A small pump pushes water through a hose to another container inside the bathhouse. You can see its rounded corner on the left in the above black and white photo collage.

To heat the water, a small pre-fab furnace that looks like it's assembled out of ducts is fed with the kindling of ruined houses. Does anyone else find that incredibly poetic? The wood-burning furnace is a traditional way of heating water for both the home and the public sento. You can still occasionally recognize a sento in the cityscape by its smokestack.

The bathhouse is constructed out of what has suddenly become scrap. It's dark with a glazed window in the anteroom, and light seeping through the cracks between wall and roof. However, the interior is clean and spare. When the bathwater is heated, everyone takes turns bathing in the same water, beginning with the male elders, then the men, then the children, and last, the women.

We were able to document this bath after meeting another volunteer group working in a village on another part of the peninsula. We spoke to Rob-san, a carpenter originally from Seattle, who has lived in Kyoto for the past decade or so. He was leading a group of high school students from Kobe to help clean up and also to dig out the drains of the village, which are currently full of mud.

http://www.idrojapan.org/

Rob-san mentioned the bath and when I asked him about it, he introduced us to the owner. She lives with her husband in this L shaped house that backs into a hill and offers a courtyard space open on one side, pulled back from the street. In this scheme, the water is heated in a large cauldron in the courtyard. Then the water flows through a hose (mostly by gravity it seems) toward the bath. No pump was mentioned, although it seems like it would make things easier. Plans are underway to move the cauldron closer to the bathtub, but right now it's making the courtyard a nice public space and not blocking the driveway.

Inside, the bath is somewhat better lit than the first example, and as you can see, the washing machine is still in use to some extent. The space is tiny and it's difficult to imagine how to keep the towels stacked on the right dry while you pre-bathe, but I'm sure with care it can be done. The mirror offers a small homey comfort.

Conclusion

During Golden Week I visited the peninsula next to Ishinomaki as a foreign exchange student volunteer. Although of course I had seen images of the Tohoku region and the effects of the tsunami, I hadn't really understood what it was like to be there. I hadn't really understood what had happened. Visiting a village of oyster farmers helped me understand. All the furniture and photo albums and stuff from daily home life had been thoroughly mixed with the tools and equipment key to oyster cultivation, forming heaps. The volunteers had to separate the equipment from the ruined furniture. I think it was mainly by sorting the piles and picking up the oyster equipment that I really began to understand what had happened. Once I understood, I could feel a more sincere compassion.

There is still so much that needs to be done.

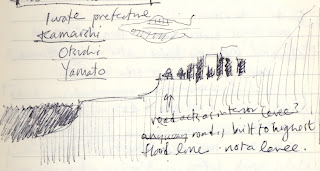

High tides inundate sunken towns

March 11 earthquake caused some places to drop by 1.2 meters

Post-Tsunami Japan: A Change of Plans? Posted May 10th 2011 at 11:24 am by Masahiro Matsuura

http://colabradio.mit.edu/post-tsunami-japan-a-change-of-plans/