Reflection on field research through volunteering

In the North, something like a renaissance is underway. Doors normally sealed tight, mouths shut and lives lived out in private have been wrenched open. This tragedy has left many homeless, or without family, or both. Some sit listlessly in school gymnasiums. Some will never be able to begin again.

But the swarthy fishermen of the Oshika Peninsula, with their stalwart wives, are making a go of it. They open their hands and ask for help. In compassion, many go North, or East, or West, as the case may be, to try and lessen the burden for these suddenly in need. I visited the Oshika Peninsula, northeast of Ishinomaki (about an hour driving north of Sendai) for the third time last week, to volunteer with the newly established non-profit International Disaster Relief Organization (IDRO) Japan.

As you must know, the disaster area is not evenly afflicted. The level of damage caused by the thick black pulses of the March 11 tsunami are directly related to local physical geography. A deep harbor absorbed the wave’s force, leaving the nearby down wrecked only by water damage. The long low sloping Sendai plane did nothing to mitigate the wave’s force. Three and a half months after the tsunami, the city feels clean and almost untouched. Driving north along the freeway we first see mountains of debris along the city perimeter and then, looking toward the ocean, hectares of fields left fruitless and salted for the next several years.

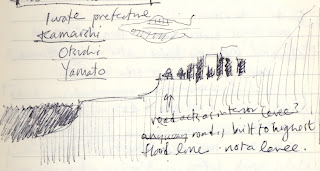

The Oshika Peninsula is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been: its lobed edge and mountains rising steeply out of the sea reminding one of an earlier Puget Sound, a milder Vancouver Island. Rounding each turn we see a new and stunning spatial condition: another perfect little harbor. Each harbor is divided into three zones: the sea, a band of village, and the forested hills. A further delineation now scores a datum into the three zones: the high water mark. In a narrow valley, this mark runs further inland. Along a river, the wave constricted and intensified, leaving houses wrecked far from the sea. In an older settlement, the mark coincides with the main road: rebuilt after the datum of the last tsunami (Chilean Earthquake, 1960) or perhaps the one before that (Showa Tsunami, 1933). A fellow IDRO volunteer named the datum: the Heaven and Hell line.

The resilience of the forests and birds, and the apparently optimistic forgetfulness of the sea make the wrecked village all the more pathetic. The arbitrary datum leaves a surreal landscape: larger, more sturdily built public buildings like the fish processing warehouse or the elementary school are structurally intact and can be occupied above the second or third floor. In Funakoshi village we are lodged on the third floor of the comparatively grandiose elementary school while we build a public bathhouse. Here, all is normal, not a book out of place, the maps hanging quietly on the walls, pedagogy a stillness in the air. The fantasy lasts to the stairwell or the windowsill, then dies. Late at night, I must go outside to use the toilet. Descending the three floors of stairs I will myself not to shine my flashlight too inquiringly into the dark rooms on the lower floors. I will myself to avoid the visions of seaweed and children.

Locals are not so skittish. Sitting around a low fire, a young man remarked to his fellow (another in my volunteer group),

“Did you see that ghost?”

“No,” said the American.

“It was a child, I think, but it didn’t want anything, it’s just hanging around.”

The notched hinoki cedar columns and beams of some of the fine old houses backing into the hills managed to evade destruction. These remaining structures have become a dense base for survivors willing to begin again. In two villages I visited, I had the chance to meet the local leaders of the recovery planning. Both boast immense personalities with rich and interesting personal histories built up as they plied their way through seven seas as sailor, fisherman, or signaler of freighters. Both occupied houses only mildly damaged by the tsunami. Perhaps they were appointed by the local government before the disaster, as is the case with some new leaders in the north, but it seemed to us that they were the somewhat peripheral members of the village stubborn enough to stick it out.

In the recently reconfigured villages in the coastal region, some survivors crowd into the remaining houses. Usually, the person who has stepped forward to lead is a middle aged male. Other former residents live with children or other family members in Ishinomaki, but commute daily to places like Funakoshi to continue the harvesting and processing of wakame seaweed. Volunteers generally stay in the largest, best preserved public building. At this point, electricity has come online everywhere as far as I can tell, and the water supply is returning as we speak. Sewers and drains are largely still clogged by thick mud, so emergency toilets have been distributed to many hamlets.

When we imagine what it must be like from the undamaged luxury of Kansai (southwestern Japan), we are fed by a slowly decreasing trickle of images from the media. Discussing perspectives and opinions with my students at the English school where I work part time, I get a sense for public opinion. Long term residents in Kobe can remember living through earthquake recovery, but admit that this situation in northeastern Japan (Tohoku) is much worse. In general, people are frustrated with the ineffective actions of the Prime Minister and the lack of a strong, clear vision for recovery. Some are shocked at the inappropriate light heartedness shown by the Prime Minister at a recently stalled meeting. Others are unimpressed with the superficial coverage offered by mainstream news media when compared to reports surfacing from volunteers and visitors via online social networking.

I mentioned a renaissance. I refer to the voices of the social media (many young, educated, urban) and their collision not only with the formerly introverted aging fishing communities of the north, but also with other volunteers. These include many self contractors who work in spurts: in a way the cowboys, renegades, and outcasts of contemporary society. Finally, it is the collision of these young pundits and activists with one another that fires this renaissance. Those who were socially conscious ronin[1] have found a clear and simple task: digging Tohoku out of the mud and then talking about it.

There are a handful of volunteer organizations channeling labor to the North. They are distinguishable by their level of logistical organization, their strategy, and their inclusiveness (native Japanese, fluent in Japanese, of Japanese heredity, foreign living in Japan, or foreigner visiting Japan: each must self-identify and seek out the aid organization capable of transporting, housing, and directing her). One of the largest aid organizations in Japan is the Nippon Foundation. Funded by a percentage of the annual takings of all gambling institutions in Japan, the Foundation not only offers direct aid but coordinates volunteer groups and funds a litany of small NGOs.

In my first two visits, I volunteered with an NGO called Nikkei Youth Network, focused on strengthening ties between Japan and anyone identifying a strong interest in Japan through service and social media. We were rolled into a larger group of college aged Japanese volunteers led by the organization Gakuvo. The visits were highly structure, almost militaristic: or perhaps simply conducted like a Japanese school trip. We traveled in buses, took regular breaks, and worked in general 6 hours a day until 3 pm. On the first visit, I met Kurosawa-san. He was my first indication that the recovery effort was not as strict and methodical as it first had seemed. We hopped into his messy van and he revved the engine, white towel wrapped around his head like a ramen chef, small round dark glasses in place. he drove us on a tour all around the peninsula, giving us an idea of the scope of the damage and the range of the responses from combination of locals and aid groups. Slowly, we pieced together that he is humbly in charge of the whole Nippon Foundation operation in Oshika and Ishinomaki.

One person he wanted us to meet was a fellow Seattleite, a carpenter named Robato-san. Robert Mangold, a former marine from Bainbridge Island, settled as a civilian in Kansai in 1995, in time to help the recovery after the Great Hanshin earthquake in Kobe. He is extremely amiable, speaks perfect Japanese, runs an antique business in Kyoto, and prefers notching to nailing his beams together. Rob is the director of IDRO, Japan. He says,

“IDRO's tactics focus on direct action in small communities often overlooked by the blanketing strategies of larger organizations. By forging ties with local leaders we are able to tailor relief to support individual needs. It is these relationships that allow us to match relief in whatever form that takes to the ever-changing environment of the area in question. Our aim is not to create dependency but to cultivate the self-reliance of these communities, so it is paramount that we work with the community instead of for or in lieu of the community. Every job is done with the help of the community.” Mangold and Kurosawa originally met in early March at a meeting organized by the local government. Unlike the local government, Mangold and Kurosawa agreed that well-timed, direct action on a small scale would help surviving communities the most. Mangold started his own cadre of volunteers when he became frustrated with the work ethic set by the Nippon Foundation for the volunteers to avoid overworking. So Rob now comes up to the Oshika Peninsula a few times a month, bringing volunteers willing to work every daylight hour.

Others feel the same way. On my five-day trip, we met two Japanese Harley Davidson fanatics who rode up on their bikes, a scaffolder, an aid for an autistic student who also drives dump trucks, a volunteer with Japan’s version of Peace Corps currently at home from Africa on holidays, a music lover who brought us some scotch…

These renegade Robin Hoods bring with them a wide variety of practical skills: They are deployed sometimes according to logistics planned by the Nippon Foundation, sometimes as a result of a town meeting, and sometimes by simply hanging around. For an hour after lunch one day, people rummaged around in their vans or organized their tools, waiting for someone to approach and ask for help. After a while, another volunteer came up and gathered a few strong arms for a specific task. On the way we saw a lonely individual scratching at a patch of dirt aside her house. We elected that a woman might feel more comfortable receiving help from another woman, so I grabbed a shovel and joined her. After and hour of hard digging she stopped, wiped the sweat away and explained “I only do a little at a time, but I come out here everyday.” I had to respect her wish to stop, although one of the men might have stubbornly ploughed on to finish the job and really help. But between the two of us, I had no right to overpower her decision, even in a show of goodwill.

As a lone female among male volunteers, I received a close lesson in gender roles in contemporary Japanese society, which I haven’t had the opportunity to experience before. When I have worked with men or boys as laborers for a class project or another short term physical task, we work hard to ignore differences in strength. But in volunteering in Japan, men and women are sometimes assigned entirely different jobs. When they do work together, it is constantly suggested that the woman take the smaller, lighter tools. Close attention is paid to how much heavy lifting a woman does, as if she cannot judge her own ability. If one of the men wants a break, he suggests to the woman that she take one, so that he can rest without losing face. It was really difficult for me to play along with this, as I have grown up as an assertive, slightly righteous, independent-minded person. Although I can see how playing the weaker role allows the woman to attend to the needs of the group, quietly nurturing her counterparts, I only felt anger and frustration when faced with a situation I could only imagine in a single way.

Of course eventually I did tire, and reflecting that I have nothing to prove my physical prowess for, late on the last day I accepted my host’s admonishments that I not go help the others knock down a concrete wall and carry it away. “That’s men work,” I was told. I capitulated, reasoning that I could spend a little time surveying the site on my own. A few minutes later, my host, Sasaki-san, turned to me and said, “maybe you could help Mami around the house.” The Japanese was a little beyond me, all I could understand in that moment was something about Mommy. I kind of looked at him, mumbled something, and left on my own walk. Hours later, I pieced together the meaning of his words.

His wife, also known as Sasaki-san, witnessed horrific things during the tsunami. She was on her way out of town after the earthquake, since people in the region are well aware of the relationship between an offshore shiver and a colossal wave. But she turned back to get her mother-in-law, who cannot move quickly. Surmizing the situation, she took her mother upstairs, barred the door tight, sat, and waited. Then, water flooded under door and through window, rising, rising, until Sasaki-san’s wife was pressed against the ceiling; until she was holding her breath, until she was thinking her last thoughts: this is it. But that was not it for her. The waters resided. The tsunami is not a single wave but rather several waves of slightly varying intensity. This time they say there were 5 big waves before night fell and they could no longer count, having found shelter or failed to do so. After the wave was sucked back out to sea, Sasaki-san’s wife pushed her way through a shattered window frame and started up the hill toward the shelter. But her mother-in-law didn’t make it. The body was carried away and remains missing.

Sasaki-san’s wife is one of the most cordial and hospitable people I have ever met. Mostly, due to my poor Japanese, I can’t understand what she’s saying, unless she’s offering food. I read in her body position frailness, but also scrupulous manners and humble attentiveness to her guests.

We took a short car trip to pick up some fish for dinner and we did our best to make limited small talk. She pointed out sites and favorite picnic spots. She marveled at the level of destruction in the adjacent town. She shared that she has only sons, and they live in Ishinomaki, but she never sees them anymore because they’re all married and have their wives to look after them. She longs a little for a daughter who she could talk to, and give advice to. On the way back, she stopped at the only convenience store in the area. She bought 2 cartons of cigarettes, ice for the fish, and two ice cream bars. She ate hers as she drove us back in the heavy, cramped, government issued truck. “I never get to do this,” she ways. We were enjoying something simple, but we were also in a quiet conspiracy—when we returned we were more refreshed and relaxed than the others.

I can’t spot Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, but it is a great threat to the long term recovery of the people of this region. Volunteering with the Nippon Foundation, we received a short sensitivity lecture. The lecture encouraged us to be conscientiously compassionate. Some volunteers I’ve met are almost painfully reflective about the sensitivity they offer the tsunami survivors. Some aid groups attend primarily to the psychological impacts of the tsunami, using creative and experimental means. Nomadic ashiyu, or foot baths allow survivors not only to raise their core temperature, improve their circulation, and soothe and bathe their feet, but also to look into the eyes of a young, unharmed college student respectfully massaging your hands and asking after your health and daily life. The model is so poignant that it can be difficult to encourage survivors to participate at first because it means allowing oneself to be somewhat vulnerable, to expose not only bare feet but possibly some raw emotional wounds carefully ignored or repressed.

Ashiyu workshops were initially tried after the Kobe earthquake in 1995, and strategies were developed in response to comparatively minor relief efforts in ensuing years, including the 2007 Niigata earthquake. Aid groups were experimenting with different ways of engaging with the affected population, giving them a time and place to tell their stories, and forming relationships of compassion with them to bolster their recovery. They tried working side by side with locals and offering soup kitchens, but neither of these scenarios addressed the heart of the matter. And so they tried the ashiyu.

But the volunteer tour I describe here was more concerned with direct action ad physical solutions. It felt really good to realize noticeable changes in the destroyed built environment; to piece by piece put it back together again, sweep it away. It feels incredible to be asked for help and then to successfully do what is within one’s power to ease the burden of another. In appreciation, we were invited to the fisherman’s bountiful table, allowed to sleep in his house, listen to his fitful snores. Each evening was a feast, a joyful gathering to lift spirits and to thank. Selfishly, it was an amazing experience to get so close to everyday Japanese life.

But since the tasks we set for ourselves were physical, the strategy deriving from labor, I forgot about trying to be gentle, and trying to demonstrate heartfelt sympathy. Laboring and laughing together is generally good therapy for all involved and I balk at the sometimes sick sweetness of Japanese sentimentality. Yet people need the opportunity to look into a pair of eyes and say what is true for them, honey or vinegar. To do that, sometimes we need to be coddled and gently pet, or maybe just followed around the house. Like the way a toddler follows Mommy from room to room. Originally it seems that the toddler is seeking protection, but we forget in that case how nurturing it is to protect. Perhaps that’s something of what Sasaki-san meant when he suggested I “help Mommy.”

Sasaki-san is a courageous, barrel chested chain smoker in his later 50s with the expressive face of a Kabuki actor and the charm of a lady’s man. As the local leader of the fishing cooperative, he built his own workhouse by adding a steel structure onto an existing traditional wooden structure. He ordered and assembled the entire thing single handedly, over the course of three months. Quite a feat, but now its wrecked and needs to be rebuilt. Out on a walk to the seawall I run into him near his old headquarters.

“Do you want to rebuild” I ask him. He looks at me, eyes piercing,

“Yes.” Then he turns his head, focusing his entire attention on me, weighing me. I cringe a little, worried like a young girl that I have nothing to offer and I won’t measure up. I feel foolish, like I’ve asked too personal a question. Blood warms my cheeks.

“So you’re an architect?” he asks.

“Er, yes, but, you know, I still have to finish school and then take all these tests before I can really…but I’m doing my thesis project on your town and how it might be rebuilt…but its purely a design exercise, really I’m not good at this practical stuff” I blurt.

“So you’re not an architect yet?” he asks, “when?”

“O, er, maybe three years, sir” or something to that effect.

“O” he says. He changes the subject and turns to head back toward his house. I excuse myself and head out to the sea wall feeling a little impotent.

In the van on the drive back, it’s finally my turn to sleep. I’ve been keeping the drivers awake and getting them to tell stories, but now I’m just nodding off. In that confusing half sleep, it dawns on me, there are many ways to help Tohoku, and although I find it to be fun, shoveling is not necessarily my greatest potential contribution. We should each contribute according to our ability, for our mutual benefit. To the extent that we are brave enough to commit.